Markets, Myths, and Misconceptions: What I Learned from the US Paycheck Life and Japan’s 30-Year Wait

Why most investors still struggle financially, and what India can learn from America’s paycheck trap and Japan’s lost decades.

It was a rainy Wednesday evening in June, those quiet hours when the streets glisten, the air smells of wet soil, and your thoughts grow louder than usual.

I had just wrapped up another intense session of CFA Level 1 prep. My screen was still glowing with terms like “monetary policy transmission” and “yield curve inversion.” That’s when my phone buzzed. That’s when a one-video notification popped up:

“Why 60% of Americans invest… but still live paycheck to paycheck.”

That headline hit me like a jolt of caffeine.

“Wait—aren’t we always taught investing is the way out of the rat race? Then why are so many people still stuck in it, even when they’re investing?”

That single question led me down a rabbit hole. A rabbit hole that connected Wall Street to Tokyo. A journey that helped me question everything I assumed about wealth-building.

When Numbers Lie — The 60% Illusion

I paused the video, opened my laptop, and dove into the stats.

Yes, it's true, about 62% of American adults have some exposure to the stock market as of 2024. Sounds promising, right?

But here’s where it gets murky.

Over 85% of U.S. stock wealth is held by just the top 10% population.

The remaining 50%? They “participate” in the market, sure—but often through employer-sponsored retirement accounts like 401(k)s, with modest balances, minimal engagement, and almost zero understanding of asset allocation, risk, or compounding.

Imagine someone investing $100/month into a target-date mutual fund, not checking or increasing it for years. They’re technically an investor, but practically, they’re passengers on a train they don’t even know the destination of.

I even found a shocking stat:

65% of millennials with investments have less than $10,000 saved.

In a country where medical emergencies, car breakdowns, or job loss can cost thousands, that’s not wealth—it’s a thin shield.

My ₹15,000 Reality Check

That’s when I turned inward.

I earn ₹15,000 per month as an intern. It's not much. Still, I allocate ₹3,000 to mutual funds every month. I track my SIPs, study market cycles, and regularly rebalance. For me, investing isn’t about the ₹3,000, it’s about learning the language of money early.

I realized something powerful that night:

“It’s not whether you invest. It’s how and why you invest that makes the difference.”

I’m building a habit, not just a portfolio.

Paycheck to Paycheck—The Silent Epidemic

Here’s where the paradox deepens.

At the same time that millions of Americans are invested in the market, around 65% are living paycheck to paycheck.

That includes many earning $150,000+ per year. These are not low-income families. They’re software engineers, doctors, and marketing execs.

How?

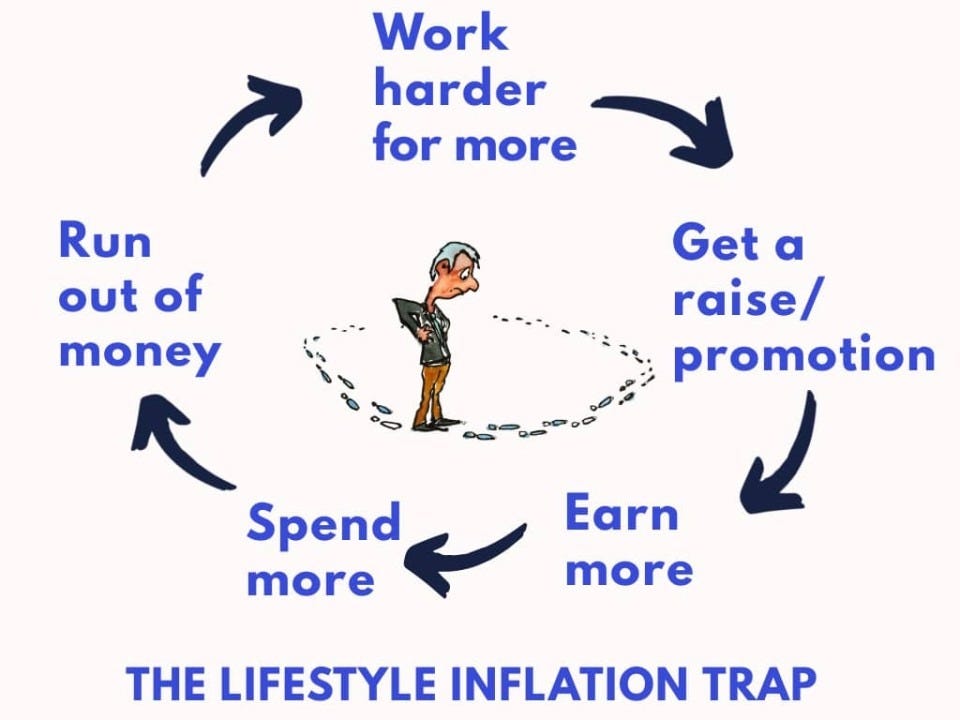

1. Lifestyle Inflation: The Invisible Enemy

You earn more, and you spend more. The old phone suddenly feels outdated, so you upgrade to the latest iPhone. That compact 1 BHK feels a little too cramped now, so you move to a bigger place. Dining out, once an occasional treat, becomes your weekend norm. With every pay raise, your lifestyle upgrades quietly, steadily.

And that’s the trap most don’t see coming:

As income rises, fixed lifestyle costs rise faster.

The ₹199 subscription becomes ₹799. The old hatchback gets replaced with a sedan. Vacations go from weekend getaways to international itineraries. Slowly, your wants start masquerading as needs. And before you realize it, you’re back to square one—waiting for the next paycheck.

One Reddit user summed it up perfectly:

“I don’t live paycheck to paycheck because I’m broke. I live paycheck to paycheck because I’m predictable.”

That line hit me hard. Because it's not poverty that keeps many from building wealth—it’s predictability. We respond to income growth with lifestyle growth. We think we’re progressing, but we’re really just upgrading the treadmill we’re running on.

And in the end, investing alone can’t outpace lifestyle inflation if we don’t manage our behavior.

2. Debt > Return

Many American households are investing their money at 7–8% expected returns… while carrying debt at 18–22% interest rates, especially credit card and student debt.

That’s like pouring water into a bucket with a hole at the bottom.

3. No Budgeting Culture

Many don’t track expenses. Financial education in schools is almost non-existent. So even those who “investing” may have no idea where their money is going or how to optimize it.

In India, especially among students like me studying CFA, we talk about DCF, IRR, and inflation premiums. But the average investor? They're told, "Just do SIP." No one tells them what it means to stay invested during a drawdown.

The US Data Behind the Illusion

Despite the US being one of the richest countries in the world, the numbers paint a worrying picture:

63% of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck, according to LendingClub's 2024 report.

Even among those earning over $100,000/year, 44% still live paycheck to paycheck.

Average household credit card debt in 2023 was over $7,200, with APR (interest rates) between 20–25%.

56% of Americans cannot cover a $1,000 emergency expense without going into debt, per Bankrate's 2024 survey.

This is despite the fact that the S&P 500 has delivered over 10% average annual returns for the last several decades.

So if the market is growing, why isn't everyone getting richer?

Because most people are not investing consistently, significantly, or mindfully. And even if they are, they’re spending faster than they’re compounding.

Want to Understand This Better? These Videos Helped Me:

Andrei Jikh – “The Harsh Truth About The Middle Class”

This video is gold for understanding why even high-income earners feel poor.Mark Tilbury – “Why You’re Not Rich Yet”

A UK-based view, but applicable worldwide. Talks about consumerism and investing behavior.

CNBC Report – “60% of Americans Still Live Paycheck to Paycheck”

This article backed up everything I was hearing in the videos. Despite wage growth, inflation and debt are pushing people back to square one. Even high-income earners aren't spared.

Read the articleInvestopedia – “Paycheck to Paycheck” (Definition + Economic Angle)

A technical yet digestible explanation of the term itself—what it means, why it happens, and who it affects.

Explore on Investopedia

My Takeaway as a 20-Year-Old Intern

I earn ₹15,000 a month. That’s not a lot. But every time I get tempted to spend on things I don’t need, just to “feel better” or “look successful”, I remind myself of one thing:

Spending makes you look rich. Saving makes you stay rich.

And when I invest ₹3,000 from that stipend, it isn’t just a transaction. It’s a statement. That I’m not going to let lifestyle creep rob me of freedom before I even earn it.

Japan’s 30-Year Mirror — The Market That Didn’t Grow

While I was processing the U.S. paradox, a classmate pinged me during a CFA mock break:

“Bro, did you know Japan’s stock market is still at the same level as in 1990?”

Wait, what?

I immediately looked up the Nikkei 225. It peaked in 1989 at around 38,900.

And in 2024? It’s still hovering around 38,500.

That’s three and a half decades of… nothing.

I couldn’t believe it. The world's third-largest economy—home to Toyota, Sony, and Nintendo—offered almost zero nominal return for an entire generation.

That sent me deep into charts, history, and a powerful case study video that laid it all out with context and clarity.

Watch: Japan's Lost Decades – A 30-Year Economic Case Study

This video helped me connect the dots — from the asset bubble to demographics to zombie companies — and made me realize that "just staying invested" isn’t a foolproof strategy. Sometimes, markets don’t reward you just for being there.

Also found this article from A Frugal Doctor. It had the perfect chart—Nikkei’s 35-year journey flatlined like an ICU monitor. The blog even mentioned that while dividends softened the blow a little, even those couldn't lift long-term returns above low-single digits annually.

“After adjusting for inflation and reinvested dividends, long-term Japanese investors made very little actual return over three decades.” – A Frugal Doctor

What Went Wrong in Japan?

1. The Bubble & Burst

The 1980s were euphoric. Japan was poised to take over the world. Asset prices, stocks and real estate, soared irrationally.

At its peak, land beneath Tokyo’s Imperial Palace was estimated to be worth more than all the real estate in California.

Then the bubble burst.

The property collapsed. Stocks collapsed. The hangover? Far worse: deflation.

2. Deflation: The Silent Killer

When prices are falling, people stop spending. Why buy today if it’s cheaper tomorrow?

Lower demand → Lower profits → Lower wages → Even less spending.

It’s a vicious loop. Unlike inflation, which erodes value, deflation freezes the economy.

Japan tried to fix it with zero and even negative interest rates, but that didn’t fix consumer behavior, or business sentiment.

3. Demographics: Old and Aging

Japan has one of the oldest populations globally.

Young people drive consumption and innovation.

Old populations save more, spend less, and are risk-averse investors.

That demographic drag is a growth killer.

4. Zombie Corporations

Japanese banks propped up inefficient companies with endless loans instead of letting them die.

These “zombie companies” didn’t contribute to growth, just survived and sucked resources that should’ve gone to new, dynamic businesses.

The Journal Entry That Changed Me

That night, I sat with my CFA notebook, on a page meant for “currency risk” notes, and wrote instead:

“Financial participation is not the same as financial independence.”

“Markets don’t owe you returns—even 30 years can go sideways.”

“Debt is a bigger enemy than a bad fund manager.”

I was shaken.

I had always believed: “Just keep investing, time will do the rest.”

But Japan showed me that time alone isn’t a strategy.

Personal Finance Isn’t Global—It’s Personal

The biggest myth I shattered that week?

“If you invest, you will become rich.”

Not true. Or at least, not complete.

Here’s what matters more:

How much do you invest

How consistently you invest

How do you control your spending

How you handle debt

How you respond to market crashes

How do you manage emotions and greed

What India Can Learn from America and Japan

As a 20-year-old CFA student in India, I paused and asked:

What can we learn from both superpowers?